BLACK FRIDAY 2022

OUR BIGGEST SALE OF THE YEAR. Up to 80% off all courses and products.

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

“All ideas are secondhand, consciously and unconsciously drawn from a million outside sources. We are constantly littering our literature with disconnected sentences borrowed from books at some unremembered time and now imagined to be our own.”

Remixing isn’t a new concept.

It’s been around for ages. So why write a guide on it?

I asked myself that question many times over while writing this. Ultimately, I realized it had to be done, because remixing is challenging.

It’s different to working on an original.

So I sent out out an email asking readers what they’d like me to cover in the guide. The most popular responses included variations of…

So whether you use FL Studio, Ableton Live, Logic Pro, Garageband or any DAW – this guide is for you.

Let’s go.

Want to read this later? Grab the FREE PDF version below!

"Official remixes are always a great way to open your mind to new ideas. When taking on someone else’s stems, you may see a new technique to incorporate into your next single!"

Remixing, as I’m sure you know, is a fundamental part of electronic music culture.

Generally speaking, the idea of a remix dates back decades.

But if we’re talking about the origins of the remix? Centuries.

Let’s have a quick look at where it all came from.

Some will argue that the birth of remixing took place with the birth of music.

You know, Gred, the caveman, came up with his own “caveman grunt” arrangement.

Then his buddy Thag came along and tried imitating him, except Thag had a stutter which caused him to effectively create a derivative of Gred’s grunt arrangement.

But this isn’t really remixing.

At least, not if we look at the purest definition of the word in the context of music:

“A version of a musical recording produced by remixing.”

True remixing (man, I almost sound as bad as a vinyl purist) was born with the genesis of recorded sound in the late 19th century.

However, music wasn’t cool back then. There weren’t any bangers.

So it didn’t really gain traction until the 1940s when real music appeared on the scene.

In all seriousness, great music was made in the 19th century, along with every century before it.

But the potential of remixing wasn’t realized until the 40s.

Accomplishments: Invented magnetic tape for recording sound.

Skills

You likely wouldn’t be reading this if it wasn’t for Fritz Pfleumer, a German-Austrian engineer responsible for inventing magnetic tape, a technology that revolutionized the world of broadcasting, recording and audio.

I won’t delve in to how magnetic tape works. I don’t have the patience and I failed science in high school.

One fun fact is that the technology was kept secret by the Nazis for a long period of time. It wasn’t until after the war that a bunch of Americans brought it out of Germany and made it commercially viable.

Moving on…

Following the advent of magnetic tape and its rise in commercial use, multitrack recording was soon developed in tandem with the experimental electroacoustic genre named Musique Concrète, which used tape manipulation to create sound compositions.

But we’re not quite there yet.

Remixing, as we know it today, didn’t begin until the late 60s in Jamaica.

Local engineers would mix, rearrange, and rebuild tracks to suit different audiences. Notables such as Ruddy Redwood, King Tubby, and Lee “Scratch” Perry made stripped-down instrumental mixes of reggae tunes, adding effects like reverb and delay to make things different.

Then, everything changed when the fire nation attacked Tom Moulton came along.

Accomplishments: Nothing major. I only invented the remix, breakdown, and 12-inch single vinyl format.

Skills

During the mid-1970s, DJs were employing creative tricks such as looping and tape edits to keep audiences interested.

But Tom Moulton wasn’t a DJ.

After making a homemade mix tape for a Fire Island dance club in late 1960s, he quickly became a key figure in the dance music industry, and went on to create what we call the “breakdown” section in music as well as the 12-inch single vinyl format.

Remixing became more and more popular throughout the 70s and 80s, taking on new forms and pushing boundaries. Today, it’s something that almost every producer dabbles in. Hence this article.

So, remixes are popular, but are they worth doing?

There’s a lot of conflicting advice on the internet, and it’s hard to tell whether it’s worth focusing solely on originals or remixes too.

While you can build a successful career and make good music without doing any remixes, you really have to ask yourself…

Why wouldn’t you remix?

…and the sooner you learn it, the better.

The ability to take something as simple as a vocal track and arrange a completely different track underneath is a skill.

The creative effort involved in taking a popular track and transforming it into something that can be enjoyed by a completely different market is a skill.

The focus required to not make a remix that sounds too similar to the original is a skill.

And guess what?

The skills you learn through remixing can be directly applied to your own productions. If you lack the connections to work with vocalists, you can practice working with vocals by doing remixes.

If you’re not great at writing melodies, why not remix a few tracks that feature great melodies and learn in the process?

Do you know how many touring artists have built their career off remixes and bootlegs?

The Chainsmokers. Skrillex. Flume. Madeon.

So how did it build their brands?

1

Remixes are a great way to build your brand because they involve more than one artist, and therefore, more than one market.

Let’s say you’re a deep-future house producer. At the time of writing this, deep house is fairly popular. It’s not foreign to the mainstream audience.

Kelsey, who’s 15 years old, isn’t a diehard fan of deep house. She doesn’t even know what it is despite hearing deep house songs on the radio. She is, however, a diehard fan of Years & Years.

You happen to write a remix of a popular track from that group and upload it to Soundcloud and YouTube. Kelsey is browsing YouTube, and because all she does with her time is listen to bands like Years & Years, she sees a video recommended for her. It’s your remix.

Because Years & Years is the other artist in the remix, you have the potential to reach fans of that artist who otherwise wouldn’t listen to your work.

2

One example of the power of remixing comes from an EDMProd follower who emailed me a while back.

He listened to episode 19 of the EDM Prodcast with Jaytech, and decided to remix one of the tracks from his album Blackout.

Jaytech liked it and played it on his radio show.

Would Jaytech have played an original track of his? Maybe, but by leveraging the artist’s name and music, he has more of a chance.

There are many more cases like this where a producer has taken initiative and made an unsolicited remix, then pitched it to the original artist or label that the original was released on.

3

Not to delve in to the intricacies of networking itself, but a great way to build your network is to start small and climb up the ladder.

Trying to become friends with Axwell by getting in direct contact with him probably won’t work unless he knows you. It’s much better to start off by connecting with people 4-5 steps underneath him and then building up.

But the ethical way to network and build friends is to offer them value first, and what better way to do that than by remixing a track of theirs?

If you write a damn good remix of someone’s track, and it becomes somewhat popular, you can leverage that achievement to do a remix of another track from an artist who’s one rung higher on the ladder.

Rinse and repeat.

I say can so that you don’t start raging.

I know what EDM producers are like when it comes to sensitive subjects like the difficulty of making a remix.

Here’s the thing. Whenever a new producer asks me whether doing remixes are worth it, I always say yes and then explain why.

In a perfect world, all new producers would focus only on remaking existing tracks for a year, but I know this isn’t going to happen anytime soon.

The reason I recommend new producers focus on remixes is because they are often easier than writing originals.

A lot of the time, you’re provided with MIDI, audio samples, ideas. You’re not starting from scratch.

This is also the reason why I recommend remixing to those stuck in long-term creative ruts. Starting from scratch is daunting, especially if you haven’t come up with good ideas in a while.

Remixing circumvents the need to come up with completely original ideas–to start from scratch–and allows you to get started with something straight away.

I still remember making my first remix.

It was for a remix competition which, because I’d been producing for all of 3 months, I obviously didn’t win.

I downloaded a remix pack containing vocals, samples, and a ton of MIDI files.

As I started the remix, I dragged in some of the MIDI files and sat there in awe…

I didn’t know you could write a melody like that!

I learned a hell of a lot, and you can bet that I wrote my next original melody in a very particular way.

Remix competitions are a massive learning resource, largely because you get access to professionally made source material. You can analyze how the artist has written their melodies and chord progressions, how they’ve processed the vocals, and so forth.

When working on remix compared to an original, you focus on a different set of skills.

When you’re writing an original track, your focus might lie in the composition – writing a great melody, crafting a chord progression, writing lyrics, etc.

When working on a remix, your focus might be on editing stems – chopping them up and manipulating them, or re-arranging them.

It might be on rewriting an existing melody, or tweaking certain notes.

The skills that you learn remixing can be applied to original compositions too, which makes remixing a great practice. You develop skills that you may not develop otherwise.

The other reason remixing is great practice is that it allows you to bypass the initial idea generation stage. When you’re remixing a track, you have ideas set out in front of you.

Sometimes, it might just be a vocal. Other times you’ll have a few MIDI tracks. At any rate, you’ve got something. You’re not starting from square one.

What this means is that if you’re going through a dry period in terms of creativity where you can’t come up with anything decent, you can do a remix. You won’t have to come up with something novel because you’ve already got a decent starting point.

Your job is to take the ideas that exist and present them in a new way.

Remixing helps you think creatively.

Yes, you have ideas given to you, but how you present these ideas is dependent on your ability to be creative.

Let’s say you’re given a deep house track to remix and you want to turn it into a drum & bass track. Doing this requires some degree of problem solving ability and creativity. It’s not an easy thing to do.

So you come up with creative solutions. You’re forced into doing something you might not have done were you working on an original.

To remix, you need existing audio material.

But you already knew that. What you might not know is how to get that material.

In this chapter, I’m going to run through several ways you can get access to stems for remixing.

"I only work with songs that I feel are great to begin with. I want to be able to hear a direction that I can take it to that isn’t the same as the song. So if it’s a really soft, sad song, I’d turn it into quite the opposite. I just take the vocal and then write a complete new original track underneath."

It’s easy to start remixes – it’s hard to finish them.

When you’re looking for remix opportunities, it’s a good idea to get clear on what you’re actually looking for.

If you produce every genre under the sun, or don’t care much for genres, then this doesn’t really apply to you.

But if you consider yourself to be a genre-specific artist (e.g. “I’m a trance producer”), then it can be worth choosing opportunities based on the style of music you produce.

Due to the nature of remixing, there’s a fair bit of wiggle-room.

A trance producer can remix a dubstep track that has a vocal, and vice versa. Why? Because they feature similar tempos (140BPM) and can share certain elements.

Most remix opportunities will benefit from multiple genres, but there’s something else that needs to be considered…

If you have a signature style, then naturally, some remix opportunities won’t be ideal. For instance, if your ‘signature sound’ is deep, dark, rolling techno, then remixing an upbeat melodic funky house track might not be ideal.

That doesn’t mean you can only take advantage of remix competitions that feature deep, dark, rolling techno tracks, it could be a more suitable genre like 140BPM tech trance, or industrial ambient/IDM music.

Another question you need to ask yourself is how difficult do you want this to be?

There’s a massive difference between making a 128BPM progressive house remix of a 175BPM drum & bass track, compared to just making the same style of remix of a 120BPM house track.

It’s just going to be easier to manipulate and manage stems (especially if vocals are involved).

If you have no other option, or simply want to challenge yourself, then the former is great. But if you want to remix for the sake of remixing, then why wouldn’t you make it easier on yourself?

Have you ever had a song stuck in your head?

Of course you have.

Songs get stuck in your head partly because they’re catchy, and partly because you listen to them a lot.

When you’re browsing through potential tracks to remix, you should listen briefly to get an idea of what they feature (in terms of vocals and composition), and then either move on or decide to remix.

What you shouldn’t do is pick a track to remix, and then listen to the original ten times before starting your remix. Doing this can severely decrease your chances of coming up with something creative.

You’ll hear the vocal, or one of the stems, and you’ll be reminded of everything else in the track. Subconsciously, you’ll end up making something similar to the original.

And even if you don’t make something similar, you’ve probably lowered your potential to make something truly unique.

Ideally, you want to scan through the original track (you don’t even have to listen to the whole thing, just click the track at certain points to get an idea), and then start on the original straight away. You’ll be forced to work with what you’ve got – you won’t have a reference.

Flume agrees – “I usually try to not listen to the original too much. I like to get the track almost out of context. That helps creating something totally different and weird.”

There are many ways to get your hands on audio material for remixing. Some approaches will allow you to work on an official remix, others will not. Some approaches require you to be a fairly proficient and established producer, others do not.

The approaches you take are up to you. But, before we get into them, a quick public service announcement…

Many artists make the mistake of choosing remix opportunities (especially those in the form of contests) based on the lack of source material on offer.

They’ll reject remix competitions that only offer an acapella. That don’t include MIDI or other stems. I’ve seen people avoid remix competitions simply because the BPM and/or key weren’t stated!

But I get it. That was me. I used to scroll through remix competitions looking for ones that had the BPM and key clearly advertised, and included a lot of stems. Why? It was nothing more than laziness – if the BPM and key were shown, and there were a lot of stems, I got to do less work.

The fact of the matter is, you don’t need everything.

If you’re doing a remix and you’ve been given every stem from the original song, it’s typically unwise to use them all, and you might even be at a disadvantage as you’ve got to fight the urge to take the easy route and use more of the original stems (resulting in a less original remix).

Often, something as simple as an acapella is all you need.

Sure, it’s more difficult to work from than a fully fledged remix package, but that’s actually a great thing – it forces you to be more creative.

So, as you look to gather material and find opportunities – don’t discount them based on what they offer. If it’s something as simple as one MIDI file containing the lead melody, then go for it.

I mentioned in the last chapter that I think all new producers should do remixes. What I didn’t mention is that it can be quite difficult if you don’t have enough source material.

I still remember trying to produce a remix from just an acapella. I gave up the first couple of times – it’s difficult.

If you are a new producer, it’s worth picking remix competitions that do offer a bit more in terms of stems and MIDI. Not only does this allow you to complete the remix more quickly and easily (and rapid output is *essential* if you want to become a better producer), but you’ll also learn a lot more in the process by analysing how they’ve composed the melodies and chords as well as put together the arrangement.

There are, of course, ways to find the original MIDI (or at least come up with some basic ideas using an acapella), which we’ll look at later on in this guide.

If there’s a remix opportunity you really want to take advantage of – don’t discount it based on the fact that you’re not going to receive a lot to work with.

I thought I’d start with remix competitions as they’re one of the easiest and most common ways to get involved with remixing.

Why? Anyone can enter a remix competition.

It doesn’t matter whether you’re tall, short, have been producing for 5 years or 5 months. Even Sony Acid Pro users can enter remix competitions.

However, keep in mind that unless you win the competition, any remix you make will not be an official remix. If you’re a newer producer, you have less of a chance to win remix competitions than those who’ve been producing for a long time, so it’s worth seeing remix competitions as a means to practice rather than win.

We’ll get into the fascinating realm of copyright law later on in the guide. Back to remix comps.

Some remix competitions are ran independently (at the time of writing this, I was a sponsor of a remix competition run by Heroic Recordings and Cymatics). Others are run through a platform like Splice.

There isn’t a huge amount of difference between independent competitions and platform-based competitions, but you can expect a lot more competition (heh) with the latter as well as a voting system.

We’ll cover the intricacies of remix competitions (and advice for winning them) in chapter 6. This chapter is about gathering material, so where can you find remix competitions to gather material from?

A social network for musicians and also a popular remix competition host, Indaba was a great way to get your hands on good material.

Recently, they were acquired by Splice, who now hosts remix competitions natively on their platform. Now you get the best of both worlds.

Similar to the model of Splice, SKIO offers sample packs as well as remix competitions, and a community to go along with it.

The best part is – it’s free, for both the samples and contests.

Although they’ve become a digital marketing and analytics tool for the music industry, Wavo still occasionally hosts remix compeititons.

Metapop aims to be more than just another remix competitions site – they act as a central hub for producers and musicians.

Simply create an account for free to start entering remix competitions and getting access to stems.

Remix Comps aggregates all major remix competitions (and smaller ones) so you can find them all in one place.

I use this site personally to find competitions, and I recommend you do as well.

As mentioned above, some remix competitions are run through platforms and others are run independently.

If you want to keep an eye out for independent competitions, there are a few ways to do it:

One way to gather material and take part in remixing is to pitch individual artists and labels.

A lot of producers shy away from doing this because they believe they aren’t good enough–or established enough–for the artist or label to care about the.

Now, it’s highly unlikely you’ll be able to effectively pitch a label like Anjunabeats or Spinnin’ Records for an official remix opportunity after producing for a mere 6 months, but there are millions of upcoming producers who’d be flattered if you asked to remix their track.

If you’re a new producer, (between stages 1-3 in this article), then it’s worth taking this exact approach. If you’re more advanced, simply change the variables (seek artists who have a bigger fanbase, etc.)

Before pitching, you need to find someone to actually pitch.

The best way to do this is to leverage music-sharing platforms like YouTube and Soundcloud. You want to be looking for artists who have a small following, as they’ll be less inundated with requests and more likely to respond. An artist with over 100,000 followers probably won’t have much time to respond to your message, and if they do, it will likely be a “no” due to contractual obligations or the mere fact that they don’t want people they don’t know to remix their work.

Let’s start with YouTube.

A great method for finding smaller artists is YouTube’s advanced search.

This method requires a bit of digging, but it’s worth it. If you simply searched “small EDM producer” on YouTube, you wouldn’t find what you’re looking for.

What you want to do is search for your desired genre (mine is progressive house) and then filter by upload date. I like to pick “Today,” but if it’s a super popular genre you might want to pick last hour.

Straight away I see an upload with 221 views, on a channel with ~8000 subscribers. After clicking through to the artist’s page, I find he has just over 500 subscribers. So far so good.

A quick Google search shows me that he has approximately 1300 followers on Soundcloud, 100 likes on Facebook, and 23 followers on Twitter.

This is an excellent artist to pitch, and it took me less than 5 minutes to find him. His Soundcloud bio tells me that he lives in England, and has a contact email address, which takes me to step 2.

The brilliant thing about Soundcloud is that it’s incredibly easy to see who follows who, and you can quickly audition someone’s music to find out what level they’re at, as well as see how well-known they are.

Let’s say I visit the Soundcloud profile of the artist I found on YouTube and decide that he’s too well-known and is probably not worth pitching. Or his bio says something like “no remix requests.” What I can do is use his profile to find other artists that might be more willing.

I scroll down to his followers (it’s often a better idea to look through the followers list rather than the list of people the artist is following, as the latter will usually include big profile artists), and start browsing.

It’s good to have a criteria for picking potential artists to pitch. You don’t want to individually click on 1300+ artists and work out whether they’re worth pitching or not.

Your criteria might be as follows:

Now, I know what you’re thinking. Sam, what about all the great artists with under 200 followers, ugly logos, and spammy names!

The thing is, you’ve got to add filters like this to manage everything. You simply can’t individually assess 1000 artists. It’s inefficient.

Before pitching, it’s worth doing a bit of study on the artist. Listen to some of their other tracks, get an idea for who they are, what they like, and so forth.

The artist I’ve found has several brilliant tracks, but I’ve picked one in particular that I want to remix, which we’ll call Memories (that’s not the real name of the track, I’m not sharing this information as I don’t want him to be bombarded with remix requests!).

Because he has a contact email address, and he’s clearly stated that it is indeed a contact email address, I’ll pitch him through email instead of Soundcloud or YouTube message (if no email address is provided then pitching through Soundcloud or Facebook message is ideal).

When pitching, it’s important to keep it short and simple. Don’t send a 500-word pitch. No one wants to read a novel. A few sentences will do.

Remember, the person your pitching will listen to your music, so make sure you’re showcasing your best work. Ultimately, your music will be the most important piece in your pitch.

I recommend watching Budi Voogt’s Art of Pitching video that I’ve posted here on EDMProd, but if you want some cliff notes, here’s what constitutes a good pitch:

Artist Pitch Template

Hi [first name],

Hope you’re well.

I just came across a song of yours on YouTube and was so impressed I just had to look into you more. You’ve gained a new fan.

My name’s Sam Matla, which is also my artist name. I primarily make progressive house and have had releases on X, Y, and Z, one of which you can listen to here (insert link).

I’d really like to remix your track [insert track name]. I had so many ideas run through my head while listening to it. All I’d need from you is the vocal stem.

Let me know if this is possible!

Warm regards,

Sam Matla

The above pitch is brief, clear, and it compliments the artist being pitched.

Note: if you don’t get a response, it’s reasonable to follow up a week or so later. Just say something along the lines of “Hey [name], just wondering if you saw this? Thanks.”

Pitching labels is slightly different, and could be deemed more difficult depending on what label you’re trying to pitch.

It’s very difficult to pitch labels without some sort of track record or back catalog. Labels not only have a ton of unofficial remixes to deal with, they also get a lot of requests for remixes, so you have to stand out.

One thing that helps you stand out is the quality of your music, and if that’s not there, then you should hold off on pitching labels, unless you want to pitch a smaller label because you really like a release on there.

Another thing that helps you stand out is a good pitch. Here’s a template you can use…

Label Pitch Template

Hi [name of A&R/manager],

Hope you’re well.

I’m [name], and I make [genre] music under [alias]. I’m a big fan of [release] and given that it’s just come out I was wondering if you’re looking for a remix.

If so, I’d love to help out. I’ve had past releases on [insert labels], have been supported by [insert key artists], and am always looking for new opportunities.

Let me know if there’s a possiblity of remixing this track or another.

Thanks for your time.

Warm regards,

[name]

Besides remixing and pitching artists or labels, there aren’t too many other ways to gather material for remixing.

One approach could be to search Soundcloud for the keyword “stems,” but if you do that, you should still really contact the owner of the stems and see if you’re allowed to remix them (you probably are, but you should still ask).

Another approach could be to use a site like Splice.

Finally, you could sample tracks, but that would mean you’re infringing on copyright and you’d have to call it a bootleg (unofficial remix).

We’ll get more into the legal ramifications of doing stuff like this in chapter 5, but it is an approach.

What if, instead of having to pitch labels and artists, you were the one who got pitched?

Well, the good news is, you can get to that level. It takes a certain level of skill and effort, but it’s possible.

So, how can you improve your chances of getting pitched?

Branding is essential. If you have good branding, you’re more likely to get approached.

Make sure you’ve got professionally taken press photos or clean graphics. A decent cover photo on all social platforms, and congruity between them all.

Make sure you’re active on Instagram, and your Soundcloud/Spotify profile doesn’t feature tracks that are too old (you should have some recent work on there).

Showcase your best work. Don’t upload WIPs just to show off your sound design skill. Upload finished tracks – labels want to hear finished work to judge your ability.

You don’t need a signature sound to get approached for remixes, but it certainly helps, as labels may feel a release would benefit from your signature sound.

There’s a reason why Madeon is one of the most in-demand remixers (at least he was last time I checked).

I’ve written about developing a signature sound in this article, and also in my book The Producer’s Guide to Workflow & Creativity.

The old adage “it’s not what you know, it’s who you know” is true.

Connections and friendships are what makes this industry work. If you don’t have them, you’re simply not going to encounter as many opportunities.

Start making an effort to build your network. Take a strategic approach (read this book).

Connect with artists at the same skill level as you and higher – you never know who knows who.

The electronic music scene is saturated. You don’t have to look far to realize that.

How do you stand out?

You make noise. Commentate on events in the industry, be controversial if you must.

Craft your own voice, your own persona. Put out content beyond music.

“A good remix keeps some aspect of the original composition, but offers a personalized twist on the presentation. For a vocal track, it’s easy to take the acapella and write an entirely new instrumental around it, but a good remix of an instrumental track where the original track can be recognized yet recreated in an entirely new light is always impressive.”

As I mentioned in the intro, when planning this guide I sent out an email to my list (you should join it by the way if you haven’t already) asking what they’d like me to cover.

Several people asked for me to explain what a good remix is. Which is incredibly hard to explain and describe, largely because it’s completely subjective.

Remixes differ too much – you could argue one remix is good because it’s completely different to the original, but you could also argue another remix is good because it keeps key elements of the original and the vibe stays intact.

So, rather than try and describe what a good remix is, I’m going to analyse 3 of my favorite remixes which I believe to be great remixes.

They all have different traits, which make them great for analysis.

Let’s get into it.

Obviously to judge the quality of a remix, we need to hear the original first.

Every now and then, a remix will gain more popularity than its original version. This happened with Felix Jaehn’s remix of Cheerleader which reached number 1 in 20 different countries. But EDX did it before that with his remix of Dinka’s Elements.

The original version is a well-produced progressive house with some nice glitchy parts scattered throughout. Here’s an overview of its structure.

It features a 40 bar intro before leading into the first bass-driven verse section. After 16 bars, a techy pluck sound comes in which lasts for the following 16 bars and is then removed again.

It builds in to the breakdown which features a serene vocal and a beautiful melody. So beautiful, in fact, that EDX took it and made it the key element of his remix. In the original, this chord progression/melody only appears in the middle of the track.

The track then builds into the familiar verse pattern heard during the intro of the track.

So, how does EDX’s 5un5hine remix differ?

The track stays at the same tempo of 127BPM, but is noticeably longer (a solid 8 minutes compared to the 6.5 minute length of the original).

We hear hints of the bassline coming in early on during the 48 bar intro, which then builds into a verse.

The verse is essentially a restricted version of the chorus. Unlike the original, where the chorus is featured in the breakdown, the remix stays the same in terms of instrumental structure throughout.

We hear the extended chord progression during the first chorus starting on bar 95, which lasts 16 bars before transitioning into the breakdown (via a tag/tension-builder).

The 32-bar breakdown brings the energy down a little before leading into the repetitive build-up. We hear a familiar chorus with a few changes (there’s a supporting pluck in there playing a melody alongside the main chords).

You’ll notice that EDX uses a techy pluck after 8 bars in each chorus, which sounds similar in style and rhythm to the one used in Verse (C) in the original version. This is a great example of taking a small idea and introducing it in a much different remix.

In summary, what does EDX do differently in the remix?

Original

Porter Robinson kicks the track off with an extremely short 4-bar intro (I’m sure there’s another word for this) that leads into a 16 bar A/B verse section.

The A section features a simple drum beat with a guitar, some FX, and distinctive Japanese vocal chops. The B section is similar but includes some highpassed strings and a different vocal chop rhythm.

We hear a breakdown earlier on, at bar 21, before the chorus. This lasts for 16 bars, with the second half providing huge contrast to the heavy chorus.

The chorus leads back into a brief verse before transitioning into a completely different bridge. This then leads into a shorter 8-bar build/breakdown before moving back into the final chorus.

What does Mat Zo do? Let’s see.

Note: trust Mat Zo to make a completely unique structure that’s incredibly hard to analyze. Ah well, enjoy!

Mat Zo’s remix features a similar intro the original, and even keeps the stuttered fill, but instead of the fill leading into the verse it leads back into the intro (the first time. The second time is builds into the chorus).

The chorus itself is a lot different to the original. Growly bass sounds accommodate the bottom end in its B section, while synth and pluck sounds move dynamically over the top.

The first chorus lasts for 16 bars (or 32 bars if you want to perceive it as double-time at 174BPM instead of 87).

It then moves into a short breakdown that builds into a complex breaks section. This lasts approximately 8 bars before building into a mellow, melodic build.

This is the part where you realize how much of a genius Mat Zo is, and how completely different this remix is to the original. The mellow build lasts for 16 bars, and you get the impression that it’ll build back in to the familiar chorus we heard earlier during bar 17.

Except that doesn’t happen, and it transitions into a much more aggressive build. Alright then. So it builds over 8 bars and you expect it to go back to the chorus, except you get this massive BRRRGHGHGHHGHHH sound instead.

The first time I heard this I felt a mix of about 5 different emotions. This growl section progresses and we hear a variation of the chorus played at the beginning.

So, other than almost everything, what does Mat Zo do differently?

Original

Now, I made a mistake and got the extended club mix, but it doesn’t really matter as it’s basically a longer version of the actual original mix. The club mix will herein be referred to as the original.

The original kicks off with a 49 bar intro before transitioning into a minimal 16 bar verse that features the catchy vocal.

A 32 bar chorus follows before moving into a much longer 40 bar breakdown (second verse). The familiar chorus follows.

Despite being a “summery” song, this track has quite high energy which is caused by the contrast between verse and chorus.

Let’s have a look at the Darius remix.

The remix is much different to the original in style. At 109BPM, it’s a chill-out track instead of a house track, and naturally is going to sound a lot different as a result.

The first 25 bars slowly build into what could be considered the chorus, but it’s really just the drums coming in. You can look at the Verse, Chorus, and Tag in the image below as one section almost.

The vocals feature a lot more reverb than the original to suit the vibe of the track better.

What’s different?

Obviously all these three remixes differ in terms of how unique they are compared to the original track.

The EDX remix of elements takes a single element – the melodic chord progression in the breakdown, and uses it as the basis for his remix.

The Mat Zo remix of Flicker keeps some elements of the original, like the intro and vocal chops, but other than that it’s a completely different track.

And the Darius remix of Sunlight is produced in a way that still places the vocal at the center of the track, but it’s much more mellow as the genre has changed completely.

These are all good remixes, yet they’ve all done something different. See how hard it is to define what’s good?

What we can say is that a good remix will clearly show that it’s a remix. That is, you can listen to the Mat Zo remix of Flicker, and if you’ve heard the original track, you’ll know that it’s a remix of Flicker. A good remix will keep important elements of the original.

“Don’t have to use everything in the remix pack. Find one (or two) of the major elements in the original that really resonates with you and use that as a major element in your remix. Either the vocal, or a synth hook… Something that will remind people of the original in a big way. But after that, make the rest of the track in your own style. That’s how you develop a signature sound.”

One could argue that remixes were born because people wanted to make popular music more “club-friendly.”

If you’re remixing a chill-out track and you play a lot of gigs, then it might make sense to turn it into something that has a dance groove. If you’re remixing a popular trance track and want people to listen to it while sipping on a glass of red by the fire, then you’ll remix to suit that purpose.

If you’re stuck for ideas, then why not try remixing for a purpose? You can turn a standard pop track into a dance track, or turn a dance track into something else. Think about what’s needed, what people want, what you want.

It’s important to understand, before looking at approaches, what the key difference in workflow are between working on remixes and originals.

Perhaps the biggest difference between producing a remix compared to an original is that you’re not starting from scratch. You have some source material, some audio, maybe a vocal.

Now, obviously when you’re working on an original you have access to this stuff too, in the form of samples or loops. But they’re completely abstract in form and separate from a larger whole. When you’re working on a remix that contains a vocal, you’ve already got guidelines such as:

Let’s unpack these.

1

If you’re working with an acapella, then the key of the track has basically been set for you. You could transpose it down a few semitones, and producers have done that with remixes in the past, but most of the time you’re going to leave the vocal untouched which means you’ll remain in the same key.

When you’re working on an original, you’ll normally come up with a key by yourself. You might default to your favorite key, or come across a certain preset or sample that works best at a certain note.

2

Most producers will keep an acapella at the same BPM or around the same BPM. You can change this – it’s not set in stone, but you have to have a good reason.

If you’re a drum & bass producer that wants to remix a deep house track, then you’ve got some work to do.

3

I’m all for optimistic thinking and exploring possibilities, but you cannot turn a screamo track into a mellow, chillstep song. It just isn’t possible.

A vocal may fit multiple different genres, but there are certain genres and styles it will work better in. If you have a female trance acapalla at 132BPM, then making a dark techno track will likely sound dissonant.

On the other hand, a slower progressive house track will probably work well, as would a melodic dubstep track.

Unlike an original, where you have to compose everything from scratch, when you’re remixing you’ve already got some ideas.

You can keep the original melody and chord progression yet still have a unique remix. The EDX remix of Elements is a good example of that. But you can also edit the melody and general composition.

The point is, you don’t need to start from scratch. If a chord progression exists, why not build on it? You don’t always need to rewrite from nothing.

A lot of people think that remixing inhibits creative thinking, but that’s simply not true.

One thing remixing offers that original production doesn’t is a point of reference. If you have an acapella, you can try out a ton of different ideas (melodies, chords, samples) and get immediate feedback.

You might write a few notes of a melody, play it against the acapella and realize it doesn’t work, so you change the notes.

It’s much harder to do this with an original unless you already have something in place. Again, you’re starting from scratch.

I know I’m making it sound like remixes are a lot easier than originals, and in some respects, they are. But at the same time – it’s really as hard as you want it to be.

You can make a very simple remix that just changes the drum pattern – that’s not hard. Or you can pull a Mat Zo and change almost everything while keeping a few elements intact.

As mentioned above, when you’re remixing you can keep the core musical elements – melody and harmony – exactly the same.

Plenty of people have done it successfully, and if it’s a remix that doesn’t have a vocal and relies on the melody as the defining element, then changing the melody too much can be risky.

Take EDX’s remix of Elements for instance. He kept exactly the same harmony/melody, but instead of having it play once in the middle of the song, he had it play throughout. He also used a different instrument and rhythm with different surrounding elements.

If you’re working with an acapella or other key defining element, then it can be worth rewriting the melody/harmony. Keeping in the same key, but writing something completely different.

Teqq’s remix of Tritonal feat. Phoebe Ryan – Now or Never does this well. Compare the melody from the original (timestamp) and the remix (timestamp).

This one seems obvious, but it’s easy not to do.

Changing genres forces you to be creative, because you normally have to solve a few problems.

For instance, if you have an acapella sitting at 130BPM that you want to use at 120BPM, you can warp it, but it might sound a bit strange. One strategy people use, especially drum n bass producers is to cut up the acapella without changing the tempo so that it plays on the beat.

The Darius remix of Sunlight is a good example of changing genres.

Sometimes, the best thing to do is strip the elements of the original back and start with less. If you’re given a remix pack containing 10 different stems and 15 MIDI files, why not pick a few instead of trying to include everything?

This goes with acapellas too. You don’t have to use the whole thing. You might want to make a remix that only features the chorus section of the vocal. Don’t feel obligated to include every single word.

One approach I rarely see used is to build on ideas presented in the original.

Let’s say you’re given a 4-bar chord progression – you could turn it into an 8 bar chord progression by changing the last chord and making it lead elsewhere, or you could repeat it but add variation during the second bracket.

This is a compromise between sticking with the original ideas and completely rewriting them. You’re using the original ideas as inspiration or as a “base” to work from.

All good tracks will have a key element.

Normally, this is a vocal, and if it’s not the vocal, it’s either the bassline or the lead melody.

Typically when you’re remixing, you want to keep this key element present. It’s what defines the track, and if you get rid of it your remix might sound too much like an original. In other words, it won’t contain enough of the original track for people to identify it.

So, if you’re given an acapella or strong melody, use that as a basis for the track. Work around it instead of trying to fit it in to an existing template.

Don’t literally reverse the structure, but try to do the opposite. If the original track features a breakdown at bar 16, make your remix have a drop at bar 16. If it has a drop at bar 32, your remix has a breakdown at bar 32.

If the original has a 32 bar chorus and 16 bar breakdown, make a remix that has a 16 bar drop and 32 bar breakdown.

You get the idea. This is another way to reduce the likelihood of making something similar.

It’s easy to make a progressive house banger remix of a progressive house banger. What’s more challenging and requires more creativity is turning a progressive house banger into a mellow deep house track.

Try to make something that contrasts in energy to the original. Labels typically love this as it allows them to cater to more than one audience or listening platform. If an original has high-energy, make a low-energy remix, and vice versa.

If you’re really struggling to come up with ideas, then why not copy the style of another track (remix or original)?

I don’t mean copy it identically, but stealing the structure and general instrumentation is fine, and a great way to avoid making something too similar.

This isn’t cheating, by the way. Musicians have been copying each other for centuries.

Congratulations on making it this far. We’re halfway through now, and on to chapter 4.

You know what that means? It’s time to get practical.

In this chapter, we’ll cover:

For the sake of brevity and the fact that the most popular DAW among EDMProd readers is Ableton Live, I’m only going to cover warping/tempo adjustment in Live.

If you use another DAW, I advise you to consult the manual, or search “sync acapella [your DAW]” in Google.

So, let’s say you’ve downloaded an Acapella that’s at 128BPM, and you want to bring it down to 120BPM. How do you do that in Live?

If the acapella doesn’t have any timing issues, then it’s a pretty straightforward process.

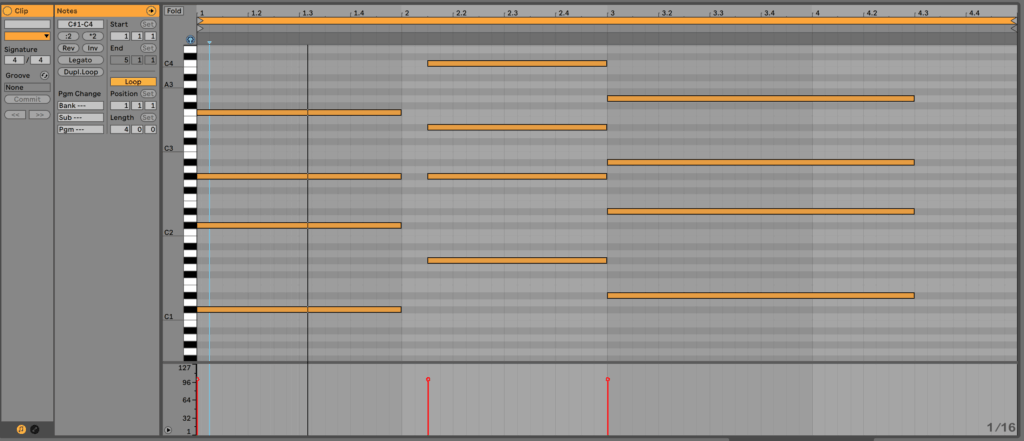

When you drag a stem into Live and click on it, you’ll be presented with the below dashboard.

You’ll see there are a number of different settings here. What we want to focus on is the Warp section.

My acapella is currently at 128BPM, and I know this for a fact. If you don’t know the tempo of your acapella, a quick Google search will suffice or you can simply use the Tap Tempo tool in Ableton (look at the top-left of your screen in Live).

I’ll enable warp and change the Seg. BPM to 128.

Note: I like to use the Complex Pro warping algorithm. It’s worth playing around with each and listening to the difference. Most people opt for Complex or Complex Pro when remixing.

Boom. Easy.

It’s worth double-checking that it’s in time, so I’ll click play and have the metronome enabled. If you do this, make sure that the acapella is actually in-time with the metronome to start with. It will always sound wrong if it doesn’t play in the right place.

Now, this acapella that I’m using is fine. I don’t have to do anything beyond this, but sometimes you’ll come across acapellas that don’t follow the same tempo throughout or haven’t been edited that well.

How do you deal with them?

There are two ways to fix timing issues with warped acapellas: manual editing/chopping, and using warp markers.

The first is self-explanatory, you simply chop pieces of the acapella and move them around so they’re on beat.

The other approach is to add warp markers to points where the vocal moves off the beat or comes in a bit too early/late.

Simply right-click above a transient and click on Insert Warp Marker(s). You’ll then be able to move this around to adjust.

Warning: this will affect the acapella as a whole. It’s sometimes a better idea to chop the acapella up individually if it’s a one-off problem. Manual warping should be used if the acapella is ridden with timing issues that manual *chopping* in the playlist can’t really fix.

We’ll go through this in more detail during the walkthrough.

I wasn’t sure about including this in the guide because it’s genre-specific, but a lot of people asked for it.

I’m going to use this technique on the Calvin Harris Sweet Nothing acapella I warped earlier. I’ve taken it from 128BPM to 120BPM.

I’ll take one phrase from this acapella and duplicate it in a new track. Here’s the section I’m using:

The next thing I’m going to do is transpose the duplicate phrase down 12 semitones and apply some EQ. This part is going to lead into the drop.

The next thing I’m going to do is transpose the duplicate phrase down 12 semitones and apply some EQ. This part is going to lead into the drop.

Finally, I chop up the vocal in the drop to make it a little more groovy.

Normally when I work with an acapella, I have a general idea of how I want the remix to sound. I won’t have the whole picture, but there’ll be glimpses of sections repeating in my head.

Taking the Calvin Harris acapella again, let’s hypothetically say that I’m making a 128BPM progressive house track with a length of around 4 minutes.

Because I have these guidelines in my head, I can drag acapella in and start pre-arranging it.

What does pre-arranging mean?

I use pre-arranging because it really comes before the arrangement. It’s a very simple starting point. I’ve only got one instrument (the acapella), but I know that it’s going to play in certain sections and be absent in other sections, so instead of arranging after I have all the instruments in place, I do it beforehand so I can fill in the gaps where needed.

As you can see below, I’ve arranged the acapella in a certain way and added markers. This is subject to change. I may move pieces around as I add in more instruments, but for now, this is the basic arrangement.

Sometimes you’ll be given an acapella without any other information. You won’t know what key it’s in, what chords should play underneath it, and while this is a great challenge for some – it’s also a nightmare for newer producers.

The most helpful thing to do in this situation is to figure out what notes constitute the chord progression or melody, and recreate them.

So, how exactly do you do that?

Your first solution should be to use Google. Unless you’re extremely quick at transcribing audio to MIDI, or you want to train your ear, then there’s no point taking longer than necessary.

Simply search for the song name + MIDI. For example: “Calvin Harris Sweet Nothing MIDI”

The first link that comes up is a link to download the MIDI file on NonStop2k. Assuming the MIDI file was good, I could download it and use it as a starting point.

Many modern DAWs will have an audio to MIDI function. If you’ve been given stems without their respective MIDI files, then it can be a good idea to use this tool to get a general idea of how it’s composed.

Note: audio to MIDI technology is not perfect yet, so you will have to clean the file up a bit, but it gives you something to start with.

Before I got into music production, I played guitar for 4 years. I still play every now and then, but I’m incredibly grateful for learning how to play.

Why?

Because if I can’t find MIDI for a popular song, I’ll look up its guitar tab (or chords). So, let’s take the Calvin Harris acapella from earlier and look at the accompanying guitar chords for the track.

There we go, the chord progression is E B G#m F#.

At this point, I can simply plug those chords in to the piano roll, adjusting where needed. If you’re following this strategy and you don’t have good theory knowledge, just Google the structure for each chord.

There are hundreds of different ways to use and manipulate stems. I’m going to cover just 4 of them, but I encourage you to experiment yourself. You can use these 4 as starting points for experimentation.

Most people think of stems as whole pieces of audio. Something that should be kept more or less intact.

A creative way to use stems is to view them as something to sample.

If you get an old jazz vinyl from the record store, you’re not going to view the song as a stem, are you? You’re going to look at it as something to sample – to extract little parts that catch your attention.

So, let’s say you have a bassline stem from the original track. Why not take one or two hits from that bassline and use them as a starting point for a more unique bassline? Or you could manipulate the sample and turn it into something completely different, like a percussive sound.

Creating vocal chops from an acapella is the same thing. You’re looking for individual parts in the stem that stick out and could be used for a different purpose.

Here are some ideas:

Stems exist to be mangled. You can completely change the vibe of a bassline stem or melody by chopping parts out.

You can take a bassline like this…

And with a couple of quick cuts, turn it into something completely different…

Seem basic? That’s because it is!

If you need to fill in your remix with a bit of atmospheric FX, one technique is to take a stem from the remix pack and chuck a ton of reverb on it to wash it out, and then place it in the background.

You can do this with vocals, synths, almost anything.

I’ll take the Sweet Nothing acapella and apply the following effects.

Before

After

Want to add a vintage feel, or simply make a stem more unique? Apply some EQ and slight bitcrushing and you can have something distinctive in no time.

Using the same vocal phrase as above, I’ll apply some EQ and Redux to get something unique.

Recommended: How To Make Lofi Hip Hop

Whenever the topic of remixing comes up, someone mentions bootlegs.

There is a difference between a bootleg and a remix, so let’s unpack that to start with.

Disclaimer: I am not a lawyer. Any advice in this post is subject to critique. If you want to know more about copyright law, please do research yourself or consult a lawyer.

A bootleg is any form of illegal or unauthorized remix or edit. If you edit a song and distribute it online or anywhere else without permission, it’s a bootleg.

If you get your hands on a studio acapella given out by the artist, make a remix with it, and put it up on Soundcloud without clearing it – it’s a bootleg.

If you have stems lying around from a remix competition 3 months ago and you decide to finally make a remix, even though the competition has ended, it’s a bootleg.

But what’s wrong with bootlegs?

As I was doing research for this section, I was taken aback by how ambiguous copyright, and fair use law, really is.

This stuff is complicated, and I don’t expect to do a great job of laying it out here, so if you are interested in learning more about this then I encourage you to do your own research.

Before understanding fair use, it’s important to realize that it’s illegal to sell, or even freely distribute music that has sampled other works unless you’ve has acquired the necessary permission to use content from such works.

Unofficial remixes or “bootlegs” fall under this, as do mashups, edits and anything using the existing recording.

What’s also interesting is that sampling another song, whether it’s a few seconds or the full arrangement, might infringe on two different copyrights–the master copyright and the publishing copyright.

The master copyright includes the recording of every stem, whereas the publishing copyright includes the composition: music and lyrics.

Most of the time, when you produce a bootleg, you’re infringing on both.

Now, some producers will cite fair use by saying that bootlegs are fine as long as you don’t include too much of the original and don’t try to make financial gain of them. This is simply not true, and fair use is less clear cut then people think.

Fair use allows artists and creatives to use parts of existing works without permission and not violate the law. A fair use might be criticism (reviewing something), commentary, reporting, teaching, or research–but the list extends beyond this.

For instance, me quoting the below paragraph from a book on copyright law and creative use would fall under fair use…

“To determine whether a particular use is fair, courts consider four factors, including whether the use is commercial, whether creative rather than factual elements of the existing copyrighted work were used, how much of the existing work was used, and whether the market for that work has been harmed.”

It’s difficult to figure out whether your unofficial remix falls under fair use unless you’re taken to court, and you don’t want that happening.

Now, it’s obvious that the majority of artists do not get taken to court over bootlegs. Electronic music producers have been making bootleg remixes for decades and very little has happened in the way of legal action.

Can you expect your bootleg to be taken down from YouTube or Soundcloud? Yes.

Can you expect a cease & desist letter? Yes.

Can you expect to be taken to court? It’s a possiblity, and I wouldn’t rule it out, but it’s unlikely.

Here are the facts:

I know what you’re thinking – how is it illegal if I don’t release it to the public?

If you produce a bootleg simply for practice and don’t show anyone, it’s still illegal. You’re infringing on intellectual property. It’s just extremely difficult to penalize.

If you’ve got this far and you’re confused, don’t worry. Copyright law is incredibly confusing. Here’s what my friend Budi Voogt had to say when I asked him about it:

“International intellectual property laws were established years ago, and there is increasing misalignment between standard industry practices and the copyright laws that are supposed to support them.”

I recommend reading Budi’s article The Indie Guide to Music Copyright and Publishing and our How To Sample Music guide for more info.

One way to work around copyright law is to produce a cover.

If you’ve produced a cover, you’ve taken the composition and arrangement from the original version of the track without taking any of the recordings/samples.

If you were to do a cover of a track containing a vocal, you’d need to re-record that vocal.

A cover version also has to be similar to the original to such an extent that it’s not considered a derivative work (a remix). However, this is a grey area and I recommend consulting a professional.

Recording and producing a cover song is not free. Here’s what Sue Basko, Lawyer for Indie Media has to say…

“The most amazing thing about recording cover songs is that the statutory royalty rate is exactly the same no matter whose song you cover. The rate is the same whether you are covering Dave Matthews or the guy who plays the local open mic. This rate is set by law. (At this time, the rate is about 10 cents per copy you will make, give away, or sell.)”

Acquiring acapellas isn’t always easy. If you want an acapella for a particular song, you’ll typically have one of three options:

There are some cases where you simply won’t be able to get an acapella for the song you want to work on. If you’re doing an official remix, you will of course be given one. But an unofficial remix? You’re on your own (in no way do I encourage unofficial remixing).

There are many different places to find acapellas for your favorite music. Here are a few:

One of the oldest and most trusted sources for acapellas. Most people will source their acapellas from here. There’s over 30,000 in total.

Quality may vary.

There’s also a fairly active forum.

Beatport has a DJ Tools category containing stems and, of course, acapella stems. You can download well-known vocals and vocal phrases for the standard track price.

Here are a few of the more popular acapellas on there:

There are also acapella packages. A few standout ones are:

These aren’t royalty free. Use them at your own risk.

To properly make a DIY acapella, you need to have the instrumental version of the track. Many producers nowadays will create a slightly different instrumental version so you can’t use phase inversion technique.

Not sure what I mean? Check out this video from School of Sounds.

If you can’t find an instrumental, you’re out of luck. The most you can do is EQ and process the full track to make it fit as best you can.

"You can’t do much with a song that’s vocal hook is on top of a full instrumental. However, songs that have the “Calvin Harris Crossover Arrangement,” where the vocal hook is in a break and a dance instrumental/drop follows it, are perfect for bootlegging. You just cut out the original drop and make your own."

Producers will rarely feature the full track in a bootleg. There may be key parts of the track feature, but given the nature of working with an original master track – some parts simply won’t fit OR shouldn’t need to be included.

Before you start digging in to your bootleg, cut up the original master track and work out what you really need to use. To do this, you need an idea of how your arrangement will be laid out and what kind of style of music you’re making.

For instance, if there’s a chorus in the original track that doesn’t have much underneath it, then you can probably include it in your chorus/drop with other elements surrounding it. If the chorus in the original track is too busy, you may need to have it featured in your bootleg as a separate section that builds into your own drop.

If you’re working with the original master track, you’re going to need to use EQ. There’s simply no way you can put a drum beat and bassline underneath the original master track without resulting in horrendous clashing.

Typically, you’ll want to filter out most of the low-end, but you may also want to give a small boost around the mids to make it pop through a little more.

One thing’s for sure, if you practice making bootlegs, you’ll get a lot better at using EQ.

I’m not sure this needs to be added as I’m sure most of you will do it anyway, but looping parts of the original track is a great way to add a touch of flavour to your bootleg and show off your production chops.

You could progressively loop a section during your build-up, or include a short sample of a solo vocal section in your intro.

This is perhaps the most enjoyable part of bootlegging.

Go through the original track and sample as much as you can. Actually view the original master as something to be sampled.

You might like the kick drum being used, so you keep that for your bootleg. You might take the chord hits and rearrange them to create a different progression. You might take a short vocal snippet, chop it up, and create a melody from the individual slices.

There are certain limitations to working with an original master track, and one of them is that you can’t add too much.

A drum beat, bassline, and new synth pattern may be enough. Some of the best bootlegs don’t feature much else. Just don’t go ahead and try to add 50 new layers to a track that already has over 20.

I mean, there have been bootlegs that add nothing more than a new drum beat. Do I think this is creative? No, but it’s still something new.

Remix competitions are a wonderful thing. They provide opportunities for upcoming artists to get attention and put themselves in the spotlight, and they allow newer producers to get access to professionally-made material and study how it’s been put together.

However, they aren’t easy to win.

In this chapter, I’m going to talk about when you should start entering remix competitions, how to find suitable ones, and how to improve your chances of winning them.

Let’s get into it.

My answer to this question will be double-sided.

You should start looking for remix competitions and downloading remix packages the day you start producing, ideally. There is much to be learned from other artists, and having access to work they’ve put together is invaluable.

I’ve learned a ton from simply downloading remix packages containing audio stems and MIDI files and studying them.

So, if you’re a new producer, or your production chops aren’t really up to speed, you should be downloading remix packages and learning from them.

But should you be entering the competitions?

This is where I can’t provide a definite answer. There isn’t any downside to entering remix competitions as a newer producer. You might not win, but there aren’t really any negative repercussions, and you might gain a few followers from them.

So, my answer is yes, enter them. Just don’t become obsessed with the idea of winning them.

So you’ve been producing for a few years and you want to try your hand at some remix competitions.

The question is, where do you start? What competitions do you enter?

A lot depends on your goals and the style of music you want to make. For instance, if your goal is to build your brand and your audience, then entering small remix competitions may not be the best way to go even if you have a higher chance of winning.

If your goal is to get a few releases under your belt and build some connections, then smaller remix competitions may benefit you.

It’s important to note that the bigger the remix competition, the more people will enter. Given the nature of probability, the more people that enter, the more competition you’re up against. Some of the popular remix competitions have established producers entering.

Given that remixcomps.com is essentially an aggregator for all remix competitions, there isn’t much point in listing a ton of different websites out, so I recommend using that website for all your remix competition needs.

Most remix competitions will accept all genres of remixes, but that doesn’t mean it’s a good idea to submit a modern dubstep remix to a label notorious for their techno elitism.

It’s a good idea to find remix competitions in or around the style of music you produce, for two reasons:

Someone like Spinnin’ Records has an obvious sound. Think about if your music suits their sound.

So, when looking for remix competitions, keep in mind the genre or style of the label.

If you’re anything like me, you’ll go through several iterations of a remix before landing on something you like.

But the thought always remains…”what if I submitted that version?”

If the competition allows for multiple entries, why not submit 2 or even 3 remixes? Assuming you don’t lower the quality by producing more remixes, your chances of winning will increase.

The mistake a lot of producers make is thinking that if they enter several competitions at once, they’ll have a higher chance of winning at least something.

This is a mistake because if you enter multiple remix competitions at the same time, you’ll either not finish any remixes, finish poorly made remixes, or burn yourself out.

Focus on one at a time.

This is a topic of its own, so I won’t unpack it too much in this guide, but you should be seeking feedback on all your production work and *especially* when you’re looking to enter a competition.

Check these out:

Some remix competitions will give you a reasonable deadline for submission.

Let’s say it’s 30 days. It’s not a great idea to submit your remix on day 2.

Instead, leverage the deadline. Get more feedback, make tweaks, work on a second version, and submit just a few days before the deadline.

Congratulations for making it this far into the guide. I know it’s lengthy.

This is the final chapter, so I want to leave you with a number of tips you can refer back to whenever you feel the need.

Note: some of these tips may contradict each other. Their purpose is to provoke ideas. Experiment with them, use them as a basis for new techniques, and so forth.

If you’re looking for a true creative challenge, try using only the original stems. Other than adding a few drum samples if there aren’t any included, don’t use any synths or loops other than those included in the remix package.

Leverage your sound design skills to turn a stem into something completely different. Transform basslines into kick drums, vocals into synths, and so forth through the use of samplers.

Changing genres forces you to think creatively. It forces you into problem-solving mode.

Find a track you’d like to remix and change it completely. If it’s a dark techno track, try turning it into a serene progressive house track. If it’s an upbeat drum n bass track, try turning it into a filthy drumstep track.

Melodies and chord progressions can be recognized regardless of what key they’re in, so why not try your hand at changing the key of the original song?

Let’s say you want to make a more club-ready version of a particular track, and you’ve made a bass sound that works really well in the key of F. Unless there’s a vocal that really shouldn’t be transposed, you can take MIDI files and simply change the key to suit your production.

We often fall into thinking that we need to make a remix completely different from the original, but this doesn’t need to be the case.

Sometimes, it can pay to keep the remix more or less the same as the original in terms of composition and structure, but beef up certain areas or change the instrumentation.

The best example of a subtle remix is Roddy Reynaert’s remix of Sebastian Weikum’s It Moves On. Compare the original and the remix.

This seems like a stupid tip, but it really isn’t. If you remix a song you hate, you’re already going to have a ton of ideas for what to do.

You might hate the fact that the vocal is too slow, so you speed it up.

You might hate the fact that the melody includes a certain note in a certain place, so you change it.

You might hate the genre the original is in, so you make a remix in a different genre, one that you like.

You don’t want to mangle the original song to the point where your remix isn’t recognisable (in other words, it’s really just an original track).

Make sure you keep elements of the remix intact. You’re making a derivative work, not an original masterpiece.

Pick a minor instrument, element, or motif from the original track and turn it into a key element in your remix. It might be something like a vocal hook that appears once in the original.

Likewise, you can take a major instrument, element, or motif and turn it into something minor by repeating it less or using a subtle background sound.

Listening to other remixes is a great way to spark some thought and creativity. I recommend listening to remixes of the same song you’re trying to remix, or remixes of similar songs.

However, be careful when doing this as it’s easy to end up copying the remix too closely. There’s nothing wrong with being inspired by a remix and gathering a few ideas, but be wary of similarity.

Despite the size and scope of this guide, I haven’t got to everything. There are plenty more tips out there, ideas, and advice that’s worth taking in as you practice making remixes.

So, if you’re ready to learn even more, I suggest checking out the following resources.

The Producer’s Guide to Workflow & Creativity

Remixing can be creatively challenging, which is why it’s important to understand the nature of creativity as well as how to stay focused and finish your work.

My book, The Producer’s Guide to Workflow & Creativity, teaches this and more.

21 Effective Tips for Making Remixes

One of the most popular posts on EDMProd, this article provides 21 quick tips for making remixes. If you’re short on ideas, have a quick read through this and apply one or two of the tips.

If you’re trying to find the chord progression and/or key from an original you’re trying to remix, chuck it in to the Hook Theory analyzer and… magic!

A listener told me to include these, and I’m glad he did. Here are 11 calculators for working out things like:

And much more.

I want to thank you personally for reading this guide. It’s a constant work-in-progress, so the version you just read won’t be the final version.

Hopefully having read this you feel inspired to head off and work on your own remixes. Remember, all the tips and advice in the world mean nothing unless you’re willing to put in the time to experiment and practice, so make sure you actually work on remixes instead of trying to learn purely through articles and theory.

Any questions or comments can be sent via Twitter or the contact page.

Happy remixing!

– Sam

BLACK FRIDAY 2022

OUR BIGGEST SALE OF THE YEAR. Up to 80% off all courses and products.

Learn how to master the fundamentals of electronic music production with the best roadmap for new producers