Welcome to the ninth installment of our article series, Track Breakdowns.

In this series, we look at the theory and arrangement behind popular songs, ultimately showing you what makes each song work.

In this breakdown, we’ll be looking at Louis Futon – Royal Blood (feat. Keiynan Lonsdale).

Louis Futon has established his career with a range of jazz/funk influenced originals and remixes. Royal Blood is no different, as he beautifully blends together upbeat synth lines, smooth vocals, and a heavy groove.

In this breakdown, I’ll teach you three foolproof ways to add jazz color and tone to your chord progressions.

I’ll show you examples of these techniques used in this song, offering advice on how to implement them into your own music.

Trust me, these are simple techniques that anyone with just a little music theory knowledge can learn. Whether you’re writing dance music, R&B, or hip-hop, you’ll be sure to take away heaps from this article.

The Sauce

Royal Blood is in the key of Ab Major.

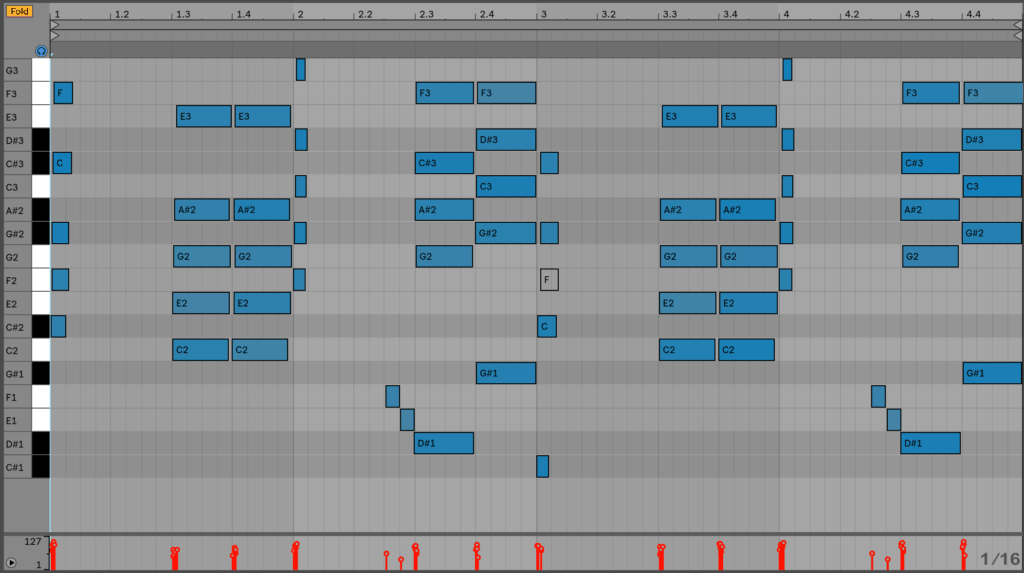

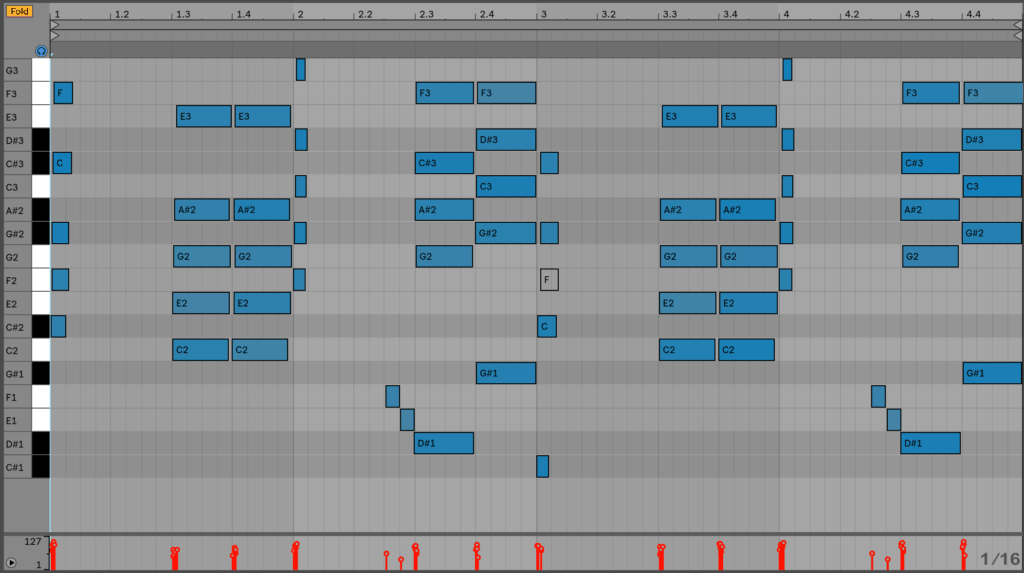

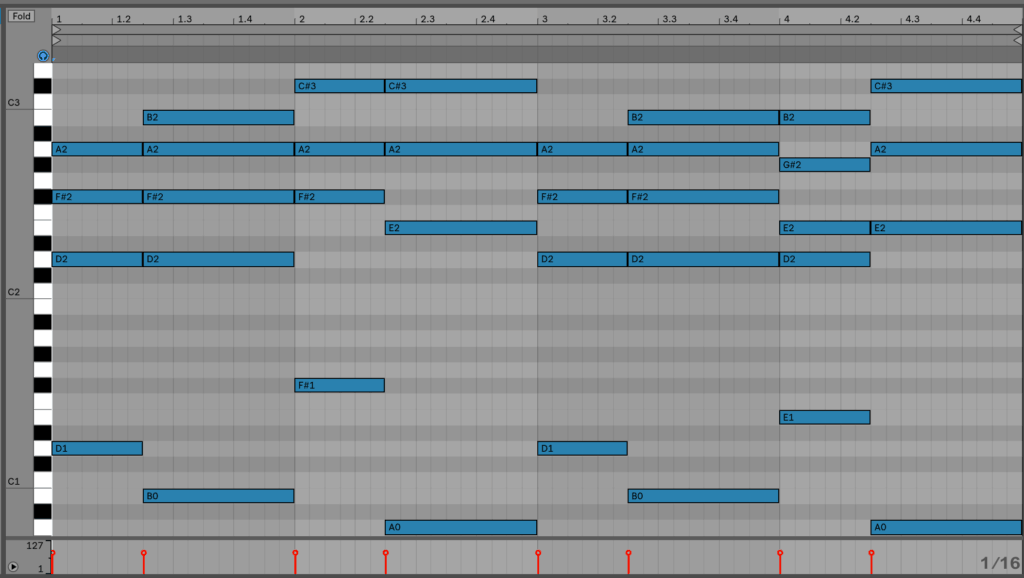

Below is a transcription of the verse chord progression:

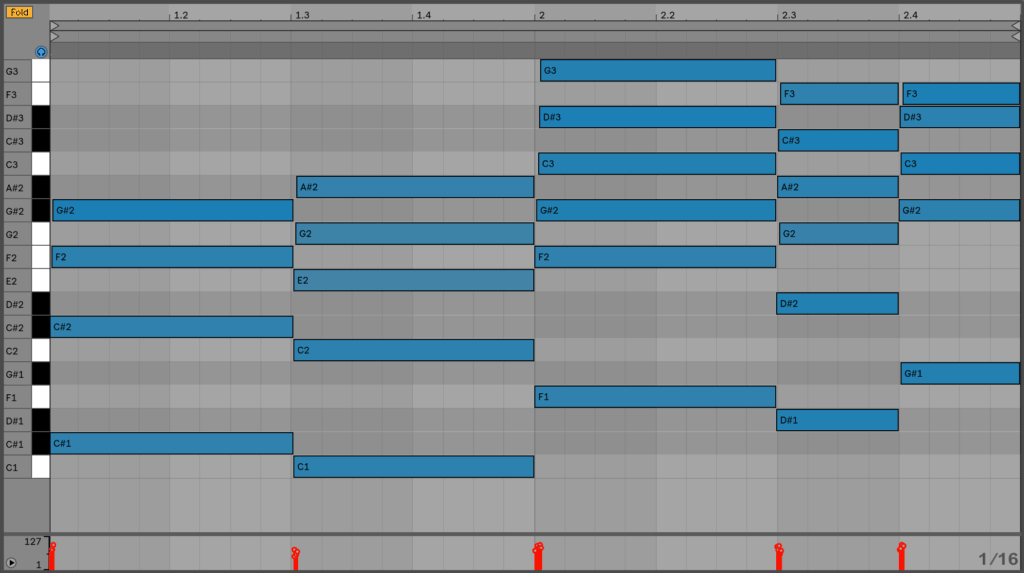

Let’s simplify this.

Below is this same progression in root position with the rhythm removed.

What are we working with?

The progression is: Db – C7 – Fm9 – Eb9 – Ab6

- Db: Db – F – Ab

- C7: C – E – G – Bb

- Fm9: F – Ab – C – Eb – G

- Eb9: Eb – G – Bb – Db – F

- Ab6: Ab – C – Eb – F

This progression sets the foundation for the entire track. It’s present in both the verses and pre-choruses. The chorus and bridge build off of it, but all share a similar chord structure and movement.

Let’s look at why this progression works, what makes it “jazzy”, and how you can spice up your own progressions.

Topics covered:

- Extended Chords – The building blocks for that a jazzy sound.

- Secondary Dominants – Nearly every jazz-influenced dance track has one of these.

- Chromatic Movement (a.k.a. Tritone Substitution) – A classic jazz chord substitution.

These names might sound complex, but the techniques aren’t.

Let’s get to it.

1. Extended Chords

What makes a chord progression sound jazzy?

If you played Royal Blood to someone with zero music theory knowledge and asked them to describe it, it’s likely that “jazzy” would pop up as a description.

Even though they have no idea what a seventh chord is, they could still hear the jazz influence.

Why is this?

The types of the chords used in Royal Blood are similar to those used in jazz.

These are extended chords.

Extended Chords – These are chords that extend beyond a three note triad. This includes sevenths, ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths.

Extended chords are a fundamental part of the jazz sound. They add an extra element of color and tension to chord progressions.

If you aren’t too familiar with extended chords, you can check out this article.

Let’s look back at the verse progression, and see what types of chords Louis Futon is using.

The verse progression is: Db – C7 – Fm9 – Eb9 – Ab6

Essentially every chord but the first uses an extension.

There is a dominant seventh chord (C7), a minor ninth (Fm9), a major ninth (Eb9), and a major sixth (Ab6).

Remember, it’s these extensions that add color to the chords, giving them their “jazz” sound.

In other words, the simplest way to make your progression sound more jazzy is to add extensions to your chords, in particular sevenths and ninths.

There are a few ways to approach this: using theory or using your ear.

A. Figure out the seventh/ninth chords diatonic to your scale.

In other words, figure out what seventh/ninth chords naturally occur in the key.

There is a pattern for this in major/minor keys, which you can learn about here.

|

Major Key |

Diatonic Seventh Chord |

|

1 |

Major Seventh |

|

2 |

Minor Seventh |

|

3 |

Minor Seventh |

|

4 |

Major Seventh |

|

5 |

Dominant Seventh |

|

6 |

Minor Seventh |

|

7 |

Half-Diminished Seventh |

|

Minor Key |

Diatonic Seventh Chord |

|

1 |

Minor Seventh |

|

2 |

Half-Diminished Seventh |

|

3 |

Major Seventh |

|

4 |

Minor Seventh |

|

5 |

Minor Seventh |

|

6 |

Major Seventh |

|

7 |

Dominant Seventh |

When writing, you can simply refer to this chart to figure out what types of seventh chord exists in that key.

For example, if you’re in F Minor, you know that the 3 chord is major (Ab major), but it also could be a major seventh (Ab major seventh).

B. Use your ear to add extensions.

The second way is to use your ear to add more notes to a chord.

This is a bit of a “spray and pray” approach, but it can be equally if not more effective than the previous one.

The execution is simple: build a basic triad, then try adding additional notes to the chord.

You could add extensions above the chord like sevenths and ninths, or within the chord itself, such as seconds and sixths.

One of the reasons this technique works is you’ll often be drawn to notes outside the scale, which is perfectly acceptable. The focus is to add harmonic texture and color to your basic major/minor triads.

One last thing.

To make a progression sound jazzier, you don’t have to make every chord an extended chord. Be careful about adding too many extensions.

I’ve seen a lot of producers learn about extended chords for the first time, then go way overboard adding ninths and elevenths to every chord in a progression. That’s a bit too much.

Try your best to find a balance between using triads and different types of extended chords.

For example, the five chords used in the verse of Royal Blood are all different: there is a major chord, a minor seventh, a minor ninth, a major ninth, and a major sixth. This creates balance and development that makes this progression memorable and exciting.

Let’s summarize what we’ve looked at so far:

- The simplest way to make a chord progression sound “jazzy” is to use extended chords.

- You can build extended chords by ear or by figuring out the extended chords diatonic to that key (there is a formula for this in major/minor keys).

- Don’t go overboard with extended chords. Find a balance between using triads and different types of extended chords.

2. Secondary Dominants.

Beyond extended chords, if you were to ask me for a simple jazzy chord progression technique, I would tell you to learn about secondary dominants.

The sound of a secondary dominant chord is unmistakable. It’s commonplace in jazz and funk, and is used readily by artists such as Lido, Medasin, and Flume.

First, let’s talk about what a secondary dominant chord sounds like.

The second chord (C7) of the verse in Royal Blood is a secondary dominant.

How would you describe this chord?

It’s quite tense, but the resolution is extremely strong.

Without diving too much into the theory behind them, here’s a short hand explanation of secondary dominants:

- The V7 – I resolution is very strong (i.e. moving from the dominant-seventh five chord to the one chord).

- This naturally occurs only once per key (since there is only one naturally occurring dominant seventh chord per key)

- We can recreate this movement by borrowing the dominant seventh chord a fifth above any chord. This borrowed chord is called a secondary dominant chord.

- The secondary dominant of G is D7, since D is a perfect fifth (7 semitones) above G.

- To use this in a progression, find the secondary dominant of a chord, then place it before that chord in a progression.

Let’s look at an example.

I have a chord progression in C Major that goes C – Am – G. I want a chord between Am and G, so I’ll use the secondary dominant of G, which is D7 (since D is a perfect fifth above G). The progression then becomes C – Am – D7 – G.

Before: C – Am – G

After: C – Am – D7 – G

The first progression sounds fine. The movement to the G chord is smooth, without any real sense of urgency.

But in the second progression that G chord sounds like it’s all we’ve ever wanted in life, and when we finally land on it we are as happy as could be.

Another way to look at secondary dominants is that they are a more exciting way to get from point A to point B. They’re a momentary detour that’s puts you right back where you want to be.

Let’s look at another example.

Often times, I’ll use secondary dominants in a chord progression the second time it loops around. This helps add interest and development to the track.

I’ll normally substitute it for the third chord, or add in just before the last chord.

Let’s look at a quick example.

Take this progression: D – Bm7 – F#m – A

To spice things up, I want to substitute the third chord (F#m) with a secondary dominant. Since the following chord is an A major chord, I’ll need the secondary dominant of A. E is a perfect fifth above A, so I can use an E dominant seventh chord, or E7.

This makes the progression (D – Bm7 – F#m – A) – (D – Bm7 – E7- A)

Take a listen below:

To summarize:

- Use secondary dominants to create a classic jazz chord resolution.

- With secondary dominants, it’s all about where you are going. Find the dominant seventh chord thats a perfect fifth above the chord you are landing on, then place it before that chord.

- You can use them in your main progression, or use substitute them in later on to add movement to a progression.

C. Chromatic Movement

Let’s jump into the chorus of Royal Blood.

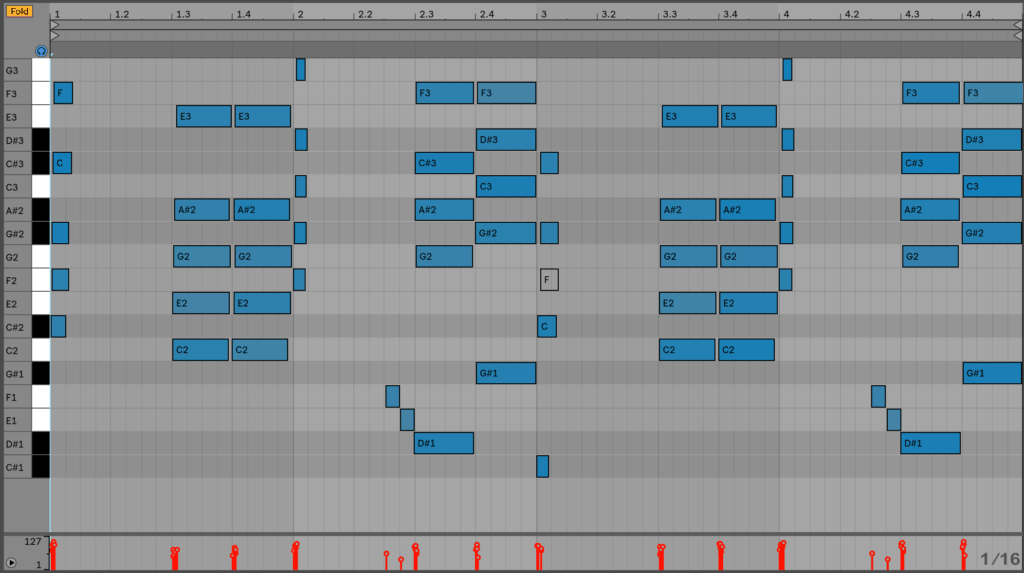

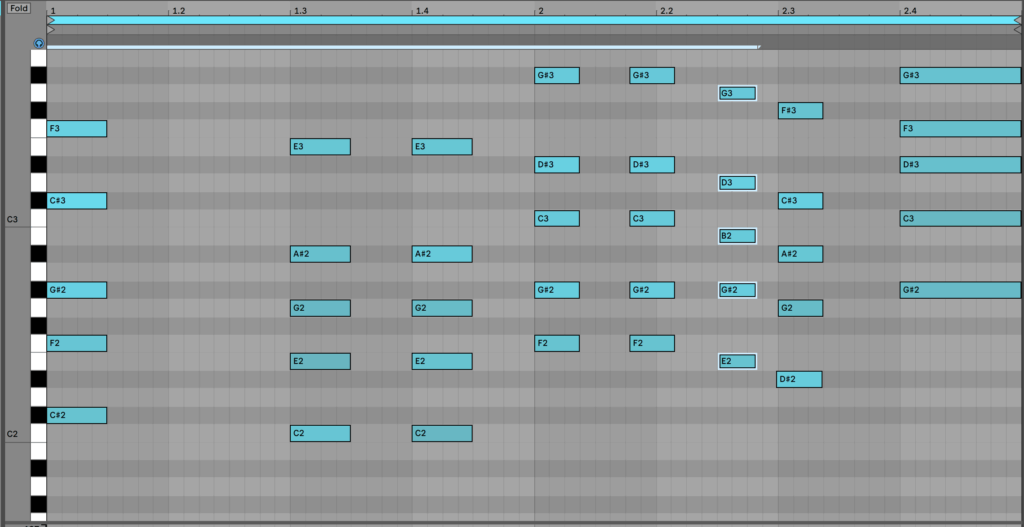

Below is a transcription of the chorus chord progression, played by the synth chords.

This progression is nearly identical to the verse progression. The rhythm is switched up, and there is one new chord added, which I’ve highlighted above.

This chord is an E7#9chord, making the chorus progression: Db – C7 – Fm7 – E7#9 – Eb7#9 – Ab7.

This E7#9 chord isn’t in the key of Ab major, so where does it come from?

There’re a few ways we can look at this.

First, we can think of it as the link between Fm7 and Eb7#9.

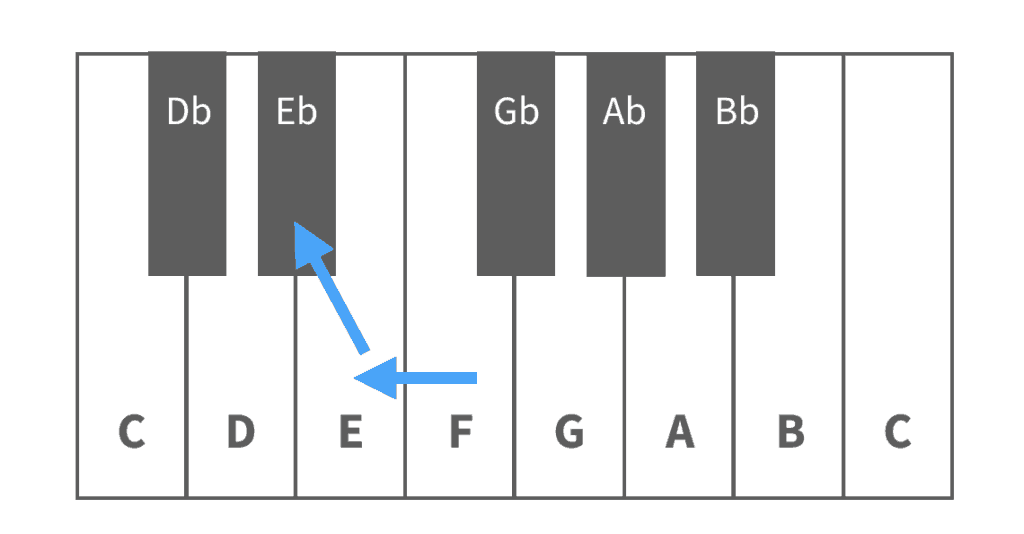

F and Eb are two semitones apart, separated by E.

You can think of this chord movement as “walking down the scale”, playing a F chord, an E chord, then an Eb chord.

So although E isn’t in the key of F minor, it makes sense in context, acting as a passing chord between F and Eb.

How can you use this information?

If you have two chords in a progression that are two semitones apart, you can move chromatically by inserting a chord rooted by the note in between them.

You’ll normally want to make this new chord a passing chord, i.e. you won’t want to hang out on it for too long.

For example, if you had an B chord then a A chord, you could play an A#/Bb chord between them. If you had an D# chord then a C# chord, you could play a D (natural) chord between them. The quality of those chords (e.g. major/minor/dominant) will depend on the context.

—

We can also approach E7#9 with a concept called tritone substitution.

The simplest way to think about tritone substitution is it’s when a dominant seventh chord resolves to a chord a half step below it.

This is a classic jazz chord substitution, and it sounds really great.

Example: A7 to Ab

Example D#7 to D

That’s exactly what’s happening in Royal Blood. We’re moving from a dominant seventh chord (in this case we also have a ninth) to a chord a half step below it.

You don’t need to understand why this works (click here if you’re curious), all you need to know is how to set it up.

The setup will be quite similar to the one discussed in the secondary dominants section (these techniques are related).

Let’s use our same C Major chord progression from earlier: C – Am – G. I want a chord between Am and G, so I’ll pick the dominant seventh chord that’s a half step above G, which is G#/Ab7. The progression then becomes C – Am – G#/Ab7 – G.

Before: C – Am – G

After: C – Am – G#/Ab7 – G

And that’s it. Although the name sounds fancy, tritone substitution is really easy to set up. Figuring out where you’re going, then place the dominant seventh chord a half step up before it.

Want free access to the Track Breakdown MIDI Vault? You can download the MIDI from all of our Track Breakdowns, as well as 25 hi-quality MIDI chord progressions you can use in your own productions.

Recap

- Extended Chords

- The simplest way to make a chord progression sound “jazzy” is to use extended chords.

- You can build extended chords by ear or by figuring out the extended chords diatonic to that key (there is a formula for this in major/minor keys).

- Don’t go overboard with extended chords. Find a balance between using triads and different types of extended chords.

- Secondary Dominants

- Use secondary dominants to create a classic jazz chord resolution.

- With secondary dominants, it’s all about where you are going. Find the dominant seventh chord thats a perfect fifth above the chord you are landing on, then place it before that chord.

- You can use them in your main progression, or use substitute them in later on to add movement to a progression.

- Tritone Substitution

- Tritone substitution is when a dominant seventh chord resolves to a chord a half step below it (Examples: D#7 to D, or C7 to B.)

Conclusion

I hope you were able to take away some useful tips and techniques from this article.

I tried to pull out as much valuable information as I could from this song, helping you to better understand what makes a great song, great.

Lastly, if there are any songs you’d like covered, please let me know!

Want to read more breakdowns? Click here to visit the Track Breakdown Glossary.

[x_author title=”About the Author”]